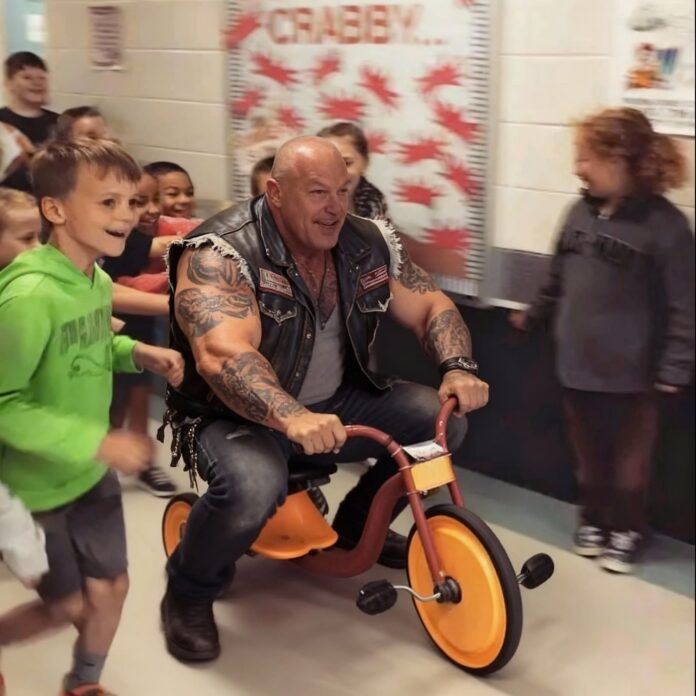

I’m Sarah Mitchell, the new hospice director, and I watched this 6’5″ tattooed man with a gray beard pedal past my office while eight bald children in wheelchairs chased him, screaming with joy.

Children who have days left to live.

“Who is that man?” I asked the nurse.

She smiled. “That’s Robert ‘Monster’ McGraw. He’s been coming every Tuesday for nine years. Ever since his grandson died here.”

I watched him crash the tricycle on purpose. Watched him sprawl dramatically on the floor while the children piled on top of him, laughing. This massive man covered in skull tattoos letting dying kids use him as a human jungle gym.

A little girl tugged my sleeve. She was maybe six, bald from chemo. “Are you going to make Monster leave?” Her eyes filled with tears. “The last director tried to ban him because parents said he looked scary.”

My heart stopped. “What?”

“She said his tattoos frightened people. That men who look like that shouldn’t be around children.” The girl started crying. “But Monster isn’t scary. He’s the only person who doesn’t look at us like we’re already dead.” I knelt down so I was eye-level with the little girl (her name tag read “Lily”). Her lip trembled, and the sight of those huge tears on such a tiny, brave face cracked something open inside me.

“No, sweetheart,” I said, brushing a stray tear from her cheek. “Monster is never leaving. Not while I’m here.”

She searched my face like she was checking for lies, then threw her thin arms around my neck so hard it almost hurt. Over her shoulder I saw Robert still on the floor, eight kids swarming him, tugging his beard, climbing his tree-trunk arms like he was the safest mountain in the world.

When the pile finally dissolved into giggles and wheezes, Robert climbed to his feet, dusted off his leather vest, and rolled the pink tricycle back toward the playroom. That’s when he noticed me standing in the hallway with Lily’s hand still gripping mine.

He froze. The man who’d just let himself be tackled by a small army suddenly looked unsure, almost shy. He gave a small nod, the kind of a question.

I walked over. Up close he was even bigger—six-five easy, arms like bridge cables, gray beard down to his chest, ink from his jaw to his knuckles. Skulls, roses, a Harley eagle, a tiny faded unicorn one of the kids had apparently drawn on him in purple marker last month that he’d refused to wash off.

“Mr. McGraw,” I said, extending my hand. “I’m Sarah Mitchell, the new director.”

He wiped his huge paw on his jeans before taking mine gently, like he was afraid he’d break me. “Ma’am. Kids causin’ trouble?”

“Only the best kind,” I said. “I hear you’ve been doing this every Tuesday for nine years.”

His eyes—pale blue and surprisingly soft—dropped to the floor. “Started after my grandson Jamie… after he didn’t make it. He loved that stupid tricycle. Thought maybe I could pay the happiness forward, you know? One ride at a time.”

Lily tugged his hand. “Tell her about the promise, Monster.”

Robert cleared his throat, embarrassed. “Jamie made me swear that if he couldn’t ride his trike anymore, I had to keep riding it for him. Said it wasn’t fair for it to sit in a closet gathering dust when other kids might need laughs.”

I felt my eyes burn. “Well, Mr. McGraw—”

“Robert. Or Monster. Everybody calls me Monster.”

“Robert,” I said firmly, “I want you here every Tuesday. And Thursdays if you’ve got them. And any other day you feel like showing up. In fact…” I turned to the nurse who’d been watching with a knowing smile. “Clear the biggest room we have on the pediatric floor next Saturday night. We’re throwing a party. Monster’s the guest of honor. Tricycle races, pizza, the works. Every kid, every family, every staff member who wants to come.”

Robert’s mouth actually fell open. “You don’t have to—”

“I want to,” I said. “And one more thing.” I reached into my pocket and pulled out the director’s master key card—the one that opens every door in the building. I pressed it into his hand. “This is yours now. You come and go whenever you want. No check-in desk, no permission slips. This is your house too.”

For the first time, the big man looked like he might cry. He stared at the key like it was solid gold, then at me, then at the circle of bald, beaming kids around us.

Lily raised both arms. “Group hug!”

Twenty minutes later I was flat on my back in the hallway, buried under laughing children and one very careful giant who kept murmuring “easy, easy” every time someone landed on my ribs.

And somewhere in the pile, Robert’s deep, rumbly laugh mixed with the higher, brighter ones, and I thought: this—this—is what hope sounds like.

Every Tuesday after that, you could hear the tiny bell on a pink tricycle long before you saw it. And every Tuesday, the hallways of a children’s hospice sounded a little less like a place where people come to die, and a lot more like a place where they come to live—really live—until the very last second.

Some people wear halos.

Monster just wears leather and rides a little girl’s tricycle.

Turns out that’s even better.